The battle for the soul of Asia continues today, just as it raged in 1932 and 1933 when Yi Kwang-Su published his epic “The Soil.” What is the best path toward modernity? How can society create harmony between the globalized city and the conservative heartland? How is nationalism a response to colonialism? Yi Kwang-Su (1892-1950) (이광수, 李光洙) touches on all of this as his protagonist, Heo Sung — torn between two women, torn between two towns, torn between two worlds — struggles with existence in 1930s Korea.

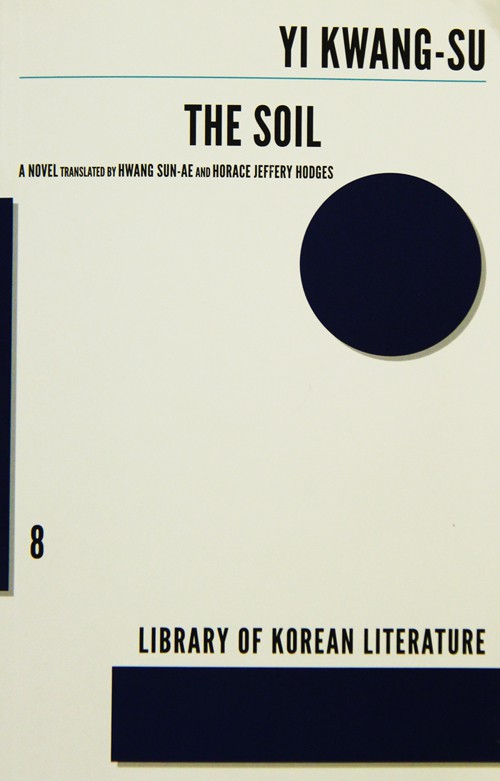

‘The Soil’ is an elemental part of the canon of modern Korean literature. Initially serialized in 1932 and 1933, it was published in English in 2013.

Heo Sung is an honest man in a corrupt world. Elite youth are being incorporated into the Japanese colonial system, trained in Tokyo, and sent back to Seoul to rule and to manage the empire, all in the name of the Yamato people. The collaborationists insult Korean traditions, sexually harass women, drink too much, abuse their wives or girlfriends and are generally rewarded with success.

As we meet Heo Sung, the death of his patron’s eldest son opens a chance for him to marry an urbane, beautiful wealthy woman. However, he still dreams of heading back to the village to marry his first love, the country girl. The grass is always greener. Nonetheless, he gives up on this bucolic dream and takes his patron’s daughter’s hand in marriage. The young lawyer now has, he believes, it all.

Originally from a poor village but with a wealthy patron in the city, he’s eventually bested by the capital Seoul, bested by a debutante wife, and bested by the blindness of an uncaring society.

Heo Sung’s nemesis, Kim Gap-jin, works for the patron’s household, too. He insults Korean literature — quite an act for a character created by a master of Korean literature — studies in Tokyo and hounds Heo Sung at every one of his honest, nationalist, quotidian steps, from Seoul back to the countryside. Heo Sung’s other adversary, Lee Geon-yeong, who comes to the fore in the second act, trained as a doctor in the U.S. He prevents Heo Sung from helping the debt-ridden, ignorant farmers as they suffer through the worst of the Great Depression, through the worst of colonial exploitation.

Heo Sung seeks “realness” and “quality,” in the abstract, and those are in short supply. He adheres to an almost socialist, Marxist, ideal, and in the second part of the novel returns to “the soil” to build a better life and to return to his first love. He longs for a Korea of the past, a mythical Korea untainted by modernity or chaos. He longs for his youth, an idealized existence that only exists in his insanely honorable mind. Modernity — specifically, trains, colonialism and globalization — destroys people.

He returns to the village only to find the ignorant peasants suspicious of his noble motives. Vice, rape and abandonment are everywhere. He finds himself bested by the countryside now, too, populated by stubborn, skeptical farmers, and misunderstood by the new woman — his first love — who doesn’t grasp his city ways. In the end, we have a deus ex machina ending, and so the curtain falls. With the final denouement, you’ll be reminded of “Anna Karenina.”

Liberation through literature

Like his contemporary, Yi writes like Hemingway: short sentences with few adjectives. His characters are almost cartoon-like in their one dimension, and the characters all show up in the first act. Like a Joseph Campbell myth, we can identify the main archetypes. There’s the bad guy dressed in black and the good guy dressed in white. There’s the nasty woman and the honorable woman. Amid these conflicts stands Heo Sung, the nuanced and naive hero struggling to build utopia, struggling to comprehend the world around him.

Yi’s 500-page epic “The Soil” was serialized in the Dong-a Ilbo, a Seoul-based daily. From April 12, 1932, through to July 10, 1933, it was published in 272 short chapters or sections. The only English-language edition of this tale is part of the so-called “Library of Korean Literature,” a collection of Korean novels and short stories put out by the Literature Translation Institute of Korea (한국문학번역원). It was translated by the husband-wife team of Horace J. Hodges and Hwang Sun-Ae. The publishers kept the serialized structure with this book, so the Odyssey of Heo Sung rolls out across the 272 sections, each about two or three pages long, divided into four parts. Yi Kwang-Su is in good company: Dostoyevsky, Dickens and Dumas all published many of their novels serially, too, in either magazines or newspapers.

The Literature Translation Institute of Korea publishes the ‘Library of Korean Literature,’ an ever-expanding collection of Korean novels and short stories published in English.

When it was published, the story was very inspirational to readers of the day. Readers od the Dong-a Ilbo were in awe of the hero, giving up the city, and returning to the countryside to help the people. Yi’s novel inspired an entire movement, called “the enlightenment of farmers” (농촌계몽). That concept remains strong today.

Yi the savior, bringing literature to the people

Yi Kwang-Su led an interesting life, to say the least, and his modern legacy is quite nuanced. He left his diaries to posterity, so that gives us an insight into his inner thinking. He was born in early March 1892 in Jeongju, Pyeonganbuk-do Province (North Pyeongan Province), halfway between Pyeongyang and the Manchurian border. Some two decades before “The Soil” was published, in the fall of 1909, 17-year-old Yi was studying at the Meiji Gakuin University, a Christian school in Tokyo. His diariesshow that he was furious at the U.S. and Japanese professors. The students there — particularly the Korean students there — were direct witness to the overt racism and to the ultra-nationalism of the day. The Japanese students at Meiji Gakuin discriminated quite harshly against the Korean students; indeed, an ethnic Korean faced racial discrimination across the Japanese isles, the Manchurian plains and even in his home on the Korean Peninsula.

Racism, of course, is simply the flip-side of nationalism. As Japan rose in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, each citizen of this new empire had a formal “race” assigned to them. Those labeled “Japanese” were tier one. The so-called “Koreans” were tier two, along with the “Manchurians/ Qing.” At the bottom were the ethnic Han “Chinese.” You were required to carry an ID card that listed your “race.” Yi Kwang-Su experienced racism and discrimination first-hand during his studies and throughout his life.

In another essay, “Recommending Reading” (1915) (“독서를 권함,” “讀書를 勸함”) — again, as translated by Gabriel Sylvian — he wrote, “I escaped from conditions of primitive poverty and base barbarism and came into an abundant, high, gorgeous civilization. What gave me the ‘great surprising correction’ to the business of the Creator is, in fact, the power of a treasure gleaned from amassing a repository of books.” Literature is salvation. Literature is modernity. Literature is independence.

In February 1919, at the age of 27, he was co-drafter of the eighth Student Declaration of Independence. In April 1919 and in response to the police crackdown after the March First Movement, he moved to Shanghai to help found the Korean Provisional Government, along with other independence activists. He was back in colonial Seoul by 1921, aged 29 years old.

Yi converted to Buddhism in the 1930s just before “The Soil” was published. He was incarcerated by the imperial police in 1937 and emerged as a collaborator himself after about 1939. Much of his writing from the 1940s onward is traditionally considered to be pro-Japanese, though a modern interpretation could forgivingly call it simply “pro-global” or “pro-modernity.” In 1950, as the North Korean forces fled northward away from Seoul, he was rounded up with some other writers and it was eventually found that he had died later that year.

by Gregory C. Eaves

Korea.net Staff Writer

Photos: Literature Translation Institute of Korea

gceaves@korea.kr