Korea has a long tradition of recording the doings of the kings and royal household in official documents.

The “Annals of the Joseon Dynasty” (조선왕조실록, 朝鮮王朝實錄), which recorded the times and reign of every Joseon king for nearly 500 years, is one of the few pieces of evidence we have of this tradition. A primary source of this size and meticulousness is rarely found when studying world history. These annals tell broadly of every king’s speech and reign, all the way down to the lives of the average people and natural phenomena. They vibrantly tell of conversations between kings and household staff and how policies were discussed and developed, helping us today to compose a vivid image of the past.

Until about 20 years ago, the royal annals were buried and unapproachable because very few modern Koreans could read or understand ancient Chinese characters. The records were only translated into contemporary Korean in the late 1980s, and it then took more than a decade for them to be available to the public. This was after the National Institute of Korean History offered the annals online and free-of-charge, treating them as a sort of public property.

This hidden, secretive world of the Joseon upper crust began to be unveiled, first, thanks to online publication and, second, thanks to one artist who has recreated the annals as graphic novels over the past 13 years. The cartoonist wonderfully describes the people and explains the historical events of the time using drawings and contemporary language, making it easier for today’s modern readers to enjoy. Though these graphic novels are easy and fun to read, it took much time and effort and was an all-consuming job for the creator Park Si Baek.

Park studied economics at university, but then worked as a political cartoonist at a newspaper. Now, he’s solely a history cartoonist.

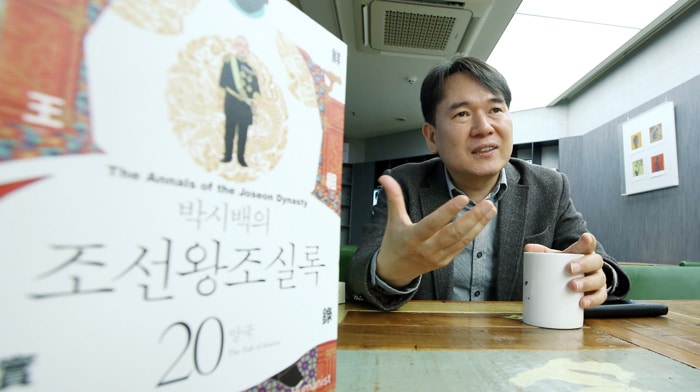

It took Park 13 years to animate a total of 2,077 volumes of the annals. It would apparently take four years to read them all if you were to read for eight hours per day. He read more than 100 books and filled 121 notebooks with hand-written notes as part of his research. Based on this, he finished about one graphic novel every six months, spending half the time reading the primary sources. Korea.net recently sat down with him to join him on his time travelling journey.

Graphic novelist Park Si Baek publishes the 20-volume ‘Park Si Baek’s Annals of the Joseon Dynasty,’ based on one of the kingdom’s best-kept primary sources. He says he was one day inspired to illustrate Joseon history when he was watching a period soap opera on TV.

You hopped on a time travelling machine and went back to Joseon. This seems in some ways to be somewhat reckless. What caused you to start this project?

To illustrate the history of Joseon, the basic idea was pretty simple. There were several versions of “The Annals” already on the market. What was really difficult and what mattered the most was that I decided to base my graphic novels on the annals themselves, on the primary sources. I had been drawing political cartoons for the Hankyoreh, a newspaper, when I first planned this project. The job was stressful. I wanted to find a job that I would be able to continue for the rest of my life.

Was it stressful?

I was drawing comic strips, not one-panel cartoons. So I had to develop stories with a twist in the last panel for every strip. I drew two to three times per week. After years of repetition, I ran out of material and new approaches. The material for political cartoons in Korea isn’t, you know, that varied: conflicts between the ruling party and the other party, et cetera. Then there’re the traditional holidays, too. I mean, it wasn’t a must, but you can’t skip it. It’s a traditional holiday. After four years of this, I completely ran out of material. Well, not exactly. The material was the same, but I ran out of new approaches and new ways to develop my art. I thought I might run out of myself, too, if I were to continue with that job for ten years or whatever. So I decided to move on to something else when I still had some energy left.

I was always confident that I was good at reproducing existing items and stories. I’d often thought about drawing educational cartoons about the principles of economics or about the Korean Constitution. As I wrote in the foreword to my version of the annals, I was inspired to illustrate Joseon history. I was watching a period piece on TV. I always enjoyed historical fiction like “Romance of the Three Kingdoms,” attributed to Luo Guanzhong, and I found Joseon history to be fun. Then at about that time, the Hankyoreh ran a story about a popular CD edition of the “Annals of the Joseon Dynasty” that would soon be released.

I remember buying it myself. It cost KRW 498,000, as I remember. The set included the “Annals of the Joseon Dynasty” (조선왕조실록), the “Memorabilia of the Three Kingdoms of Korea” (삼국사기), the “History of Goryeo” (고려사) and the “Roster of Successful Licentiate Examination Candidates” (사마방목).

Yes, you remember the price. Before even purchasing one set, I thought, “That’s it.” Reading all the books about Joseon history, they all spoke differently to me. I mean, they commented differently, and even the supposedly factual records were different. Later, I learned that this was because some of them were written based on the annals and others were written based on secondary sources. This made up my mind that I should base my graphic novel on the annals, the primary source.

Once I set my mind to it, I could see that it would take about seven years. Later, it turned out to have taken even longer, with about twenty volumes. I knew it wouldn’t be easy. Nonetheless, I was sure that this was going to be great.

Though he enjoyed reading comics as a child, Park says he never planned to make drawing cartoons and comics his profession. However, one’s life never goes as one expects. Park has now become a professional cartoonist ever since he began drawing political cartoons for newspapers.

You studied economics and don’t seem to have taken any illustration classes. Yet you’ve chosen to draw cartoons for a living.

To be honest, most of the cartoonists active today are fairly similar. People used to come to Seoul with no specific education plans. They just went to find some cartoonists and learned from them. Ever since I was little, I always enjoyed comics and graphic novels.

Which comic strips, comic books or graphic novels did you enjoy as a child?

“Babel II” by Yokoyama Mistuteru (横山光輝) is one of my all-time favorites. Masters like Go U-young, Yun Seung-un and Sin Mun-su were also some of my favorites. Anyway, I dreamt of drawing comics when I was a kid. I thought that choosing comics as my career without any university education was a bit reckless and I didn’t want to draw so much that I would skip university.

Is that why you studied drawing all by yourself?

I didn’t “study” drawing, so to speak. I just drew. I didn’t even draw a lot: maybe a bit when I was a kid, but none after that. What changed me was when I was at university. It was when students were demonstrating and marching in the streets for democracy. I drew a poster about the Gwangju democracy movement and some of my fellow students loved my work. That’s when I realized I might be able to contribute to this world with my illustrations.

Once a student of economics, then a political cartoonist and now a history cartoonist, or a historian who uses cartoons as his platform. This is a big change from political cartoons.

It isn’t really. I was able to do this because I drew political cartoons.

You have now animated the annals faithfully. It starts with Mokjo Yi Ansa, an ancestor of Taejo Yi Seong-gye (1335-1408), the founder of Joseon. Personally, I think the annals are much more honest than any other contemporary historical text.

You mean “honest” because it tells it straight about the courtesan story, with no coloring?

Yes, but it wasn’t just about a young man running away from home in the middle fo the night because of a women. It was about setting up the social structure for early Joseon. The great-great-great-grandfather of Taejo Yi Seong-gye technically migrated to Mongolia. Then Taejo Yi Seong-gye eventually returned to Korea. This is just like Korean-Americans returning to Korea. Since its founding, Joseon was an open-minded nation, accepting of Jurchen, Khitan, Mongolian and Japanese people. Later, however, the nation became closed.

Yes, you’re right. Early Joseon encouraged migration.

I assume they realized in later years that the world outside was changing. In the early days, they helped strangers who accidently landed in the nation to settle, providing a place to live and helping them to find a spouse. This changed in later years. They began to make more efforts at not allowing non-Joseon people from leaving. They seemed to be afraid of exposing their status to the outside world. However, it wasn’t like this in the early years.

The policies that the current government has to encourage a multicultural and multiethnic society are nothing like the openness seen in early Joseon. Early Joseon was a society where, for example, Muslims were allowed to wear their traditional clothes, speak their own language and cite the Quran, at least until the reign of King Sejong the Great (r. 1418-1450) (세종대왕, 世宗大王). Joseon changed with the advent of Confucianism and with the numerous attacks from its neighbors.

Yes. This might have begun when Confucian scholars, including Jo Gwang-jo (1482-1520) (조광조, 趙光祖), rose to power and started to gain a strong political following. Maybe it was Hideyoshi’s invasions of Korea from 1592 to 1598, or the Manchurian invasions in 1627 and again in 1636. Both the two sets of wars demolished everything that Confucian scholars had studied and believed. The scholars should have lost their power, to be honest, but they were able to go in an opposite direction and actually strengthen their power. Since then, the Joseon political system changed and the whole nation became closed.

However, Joseon was still able to exist for quite a long time.

This isn’t wrong. People often say there was a transformation under King Yeongjo (r. 1724-1776) (영조, 英祖) and his grandson King Jeongjo (r. 1776-1800) (정조, 正祖), but there was no real revolution and the country kept going downhill. The era when actual political power was held by one of the other upper class families, and where the monarch himself was just a figurehead, demolished the nation. Actually, this shows just how strong the Confucian scholars’ ruling system was. There was no alternative political group, nor any self-reflecting internal groups, to claim a revolution or to raise any voice.

During his research, the author filled over 120 notebooks with his hand-written notes. Due to sheer immensity of the primary source, jotting down study notes was the only way he could understand what he read, he says.

Joseon had 25 kings and two regents. Who was your favorite?

I’m always asked that question, and my answer is always King Sejong the Great (r. 1418-1450) (세종대왕, 世宗大王). First of all, he is just overwhelming. He was extraordinary intelligent and unbelievably diligent. In fact, being a prince didn’t allow him to study since that could have threatened his regality or sovereignty. Princes studied Confucian scriptures, history, and mostly, politics. This had the potential of placing them in danger of unseen enemies. So it was often suggested to princes that they spend their time doing a hobby or something. Actually, Sejong spent a lot of time on his hobbies. He played every musical instrument he could find. He collected stones. All of this, however, contributed ironically to his personal growth, as we’d say today, and enriched his artistic side.

When you see geniuses, they often turn out to be self-centered and self-righteous. They never listen to others. Sejong, however, decided every little thing through discussion. Debate was common during his reign and he listened to every member of his royal household. I believe this was an act of persuasion. Since he was so clever, he would always have a better idea than anybody else. Nonetheless, he only made decisions after listening to his staff, and once he made a decision he never questioned himself. He implemented and managed projects that took 10 or 20 years, and not only one or two of them, but several of them at the same time. In the end, he completed them all due to his initiative and to his character. Moreover, he even cared about his staff and the common people. He had every qualification a leader should have, I think.

People say that Sejong had gifted and talented people around him, and that their works enriched Joseon culturally, but all of that was technically his ideas. The publication of medical books and farming guidelines for the people, currency reforms and technological development: all of this was first designed in his mind, and then doled out to staff chosen by the king himself. Many of his descendants wanted to be like him, but his ability and capability as king was beyond their reach.

With which king do you sympathize the most?

King Danjong (r. 1452-1455) (단종, 端宗) was smart, but only had two or three years on the throne to both growup and to rule by himself: he ruled from the age of 11 to the age of 14. However, his uncle, Grand Prince Suyang, who dethroned Danjong and later became King Sejo (r. 1455-1468) (세조, 世祖), was ambitious and never hid his ambition. In fact, Grand Prince Suyang is an interesting figure. As a prince, a person in that position is supposed to behave carefully, but Grand Prince Suyang always exposed himself to politics, socialized with people and built his network. He was never restrained, he staged a coup d’état and became king himself.

The early death of Danjong, his predecessor, may have had an effect.

Maybe, but I think all of this is Sejong’s (r. 1418-1450) fault. He misjudged his son, Sejo. King Taejong (r. 1400-1418) (태종, 太宗), Sejong’s father, was the type of person who knows when the right time is. Taejong knew how to wait, and since he once staged a coup himself, he wanted his sons to enjoy brotherhood and good relationships. Sejong, however, was like a living Buddha. He actually believed his sons, in turn, would be like him. He trusted his sons to behave maturely, which later became one of his biggest mistakes. Danjong also had nobody at his side in the palace. This is why people, including myself, often sympathize with him. The way in which he was expelled from the palace by his uncle is another reason for sympathy.

This is part one of a two-part series. Part two will be published on Monday.

By Wi Tack-whan, Chang Iou-chung

Korea.net Staff Writers

Photos: Jeon Han

whan23@korea.kr