Matthew Koshmrl, the American director of the feature-length documentary “Land of My Father” about Korea’s easternmost island of Dokdo, said the island holds universal themes that go beyond nationality and race.

By Yoon Sojung

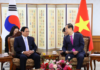

Photos = Kim Sunjoo

Seoul | Oct. 14, 2019

“The world must know about Dokdo Island, not just Korea, because it holds a universal theme that goes beyond nationality or race: resistance against a system of unfairness.”

This is what Matthew Koshmrl, the American director of the feature-length documentary “Land of My Father,” told Korea.net when explaining his film on Korea’s easternmost Island of Dokdo.

His film is in the Korean Cinema category of this year’s Jeonju International Film Festival, which runs from May 28 through Sept. 20 for online viewing. His documentary follows stories from Dokdo from the perspectives of two individuals: farmer Noh Byeong-man, the son of a forced labor victim under Japanese colonial rule, and Choi Kyeong-sook, the daughter of the island’s first resident.

Having visited the island seven times since 2014 to make his film, Koshmrl said he found very strange that Japan claims Dokdo, a Korean island, as its territory, adding that he decided to make the documentary to discover symbols of the island.

The interview was conducted in October last year, when the filmmaker came to Korea, in the Gwanghwamun area of central Seoul.

The following are excerpts from the interview.

– What made you interested in Dokdo Island?

After graduating with a degree in film studies at the University of Texas-Austin, I worked in Daegu for three years teaching English. One day, I happened to see a protest on Dokdo on the street. I saw Daegu residents so angry over Japan’s territorial claim to Dokdo. While watching the protest, I thought it was strange and questioned how Japan could continue arguing that the Korean territory of Dokdo is theirs. This question led me to make the film.

Another reason was because of my curiosity about why thousands of Koreans every year are willing to visit the island despite the long journey required of eight or more hours to get there, or if they had a special reason for going. While living in Korea, however, I realized that Dokdo Island is a powerful symbol, a symbol of the resistance of individuals against a big system of unfairness. This is more like a fight between David and Goliath.

After going back to the U.S. to my master’s in film, I still thought of making the documentary on Dokdo. And in February 2014, I decided to put into action what I had only in mind.

– Why did you choose Dokdo as the topic for your first work after receiving your master’s in film studies?

Not just because of my personal interest, I believe that many people should know about Dokdo Island because it holds universal stories for all humankind. So I took an observer’s approach when making this film that that everyone worldwide, not just for Koreans, could empathize.

Viewers overseas might initially not be aware of Dokdo Island, but it’s interesting to see the process of how they learn about the island through this film. Before finishing the movie, we did test screenings in Austin, Texas, and Korea. When Americans who didn’t know about the island saw the movie, they empathized with the subject little by little and later shed tears at the end. They understood the lone protest of Mr. Noh, who cries “Dokdo Island is Korean territory” while surrounded by Japanese police. They also understood his feelings toward Japan given the relations between his father and Japan. This is related to the victims of forced labor and wartime sexual slavery, or “comfort women,” which are still considered major issues even today. Mr. Noh has fought for all these issues, and viewers can understand and emphasize with him.

– What was your first impression on Dokdo?

When I first visited the island, I asked around for Ms. Choi, whose nickname is “Dokdo’s daughter,” to visit the island with her and learn more about it. She is the only daughter of the first Korean to live on Dokdo, Choi Jong-deok. To Ms. Choi, Dokdo is the home where she spent 12 years. Thanks to her help, I could see every corner of Dokdo during the four seasons and learn everything about the island. I found Dokdo a very unique island full of energy.

– History distortions and export restrictions have worsened Korea-Japan ties. How do you view this situation?

I’m not that aware of historical and political issues involving both countries. But I did get the chance to see related records and data while preparing to make the film. In the past, the Japanese government apologized for its historical atrocities like inflicting pain on Koreans under colonial rule. Yet I saw news that Japanese Prime Minister Abe Shinzo denied Japan’s forced mobilization of the comfort women, and even called such victims “volunteers.” I cannot understand why Japan suddenly changed its words and denied history.

– What are your plans?

Through the Jeonju International Festival and other global film festivals, I wish to introduce “Land of My Father” to many people in Korea and around the world. I also hope to live in Korea and teach film production classes. I’m deeply impressed by the Korean culture I experienced during my life here and was moved by the kindness and affection of Koreans, or “jeong” in Korean.

American filmmaker Matthew Koshmrl said he hopes to introduce his documentary “Land of My Father” not only through the Jeonju International Festival but also at many international film festivals so that the world can learn about the island.

arete@korea.kr

![[K-brand-promoting ethnic Koreans ⑤] Spreading taekwondo ‘spirit’ in Singapore](https://gangnam.com/file/2024/02/20231129124433000_ENU3D0FB-218x150.png)