Nulji brought home two brothers who had been sent into tributary-exile, made temporary peace with the rising Goguryo power, and solidified his family’s patrilineal place on the Silla throne. No statue of him exists and his tomb has yet to be discovered.

Under the reign of the two immediately prior monarchs before Maripgan Nulji (눌지 마립간, 訥祗 麻立干) (r. 417-458), the loose Saro confederation of tribes (사로, 斯盧) had gotten more organized and stronger and had taken shape as the kingdom of Silla (신라, 新羅), controlling most of what lay east of the Nakdong River. A maripgan is a sort of tribal federation chief, and it’s what the Silla people called their monarchs after the late 300s. Maripgan Naemul, the first maripgan and the subject of an earlier article in this series, was the central figure in this process. By the time his son Nulji rose to the throne in 417, a pattern of father-to-son succession had taken shape. After Nulji, primogeniture decreed that the throne only go to first-born sons.

Many of the maripgan who ruled over Silla are buried at the UNESCO-registered Gyeongju Historic Areas, mostly in mound graves, though there are some half-moon crescent graves, too. However, for Nulji, no official tomb has yet been excavated, in Gyeongju or elsewhere. His tomb is unknown.

|

Some Silla Maripgan Chieftains and Their Reigns*

17th Naemul r. 356-402 *Source: Naver, Wikipedia and elsewhere |

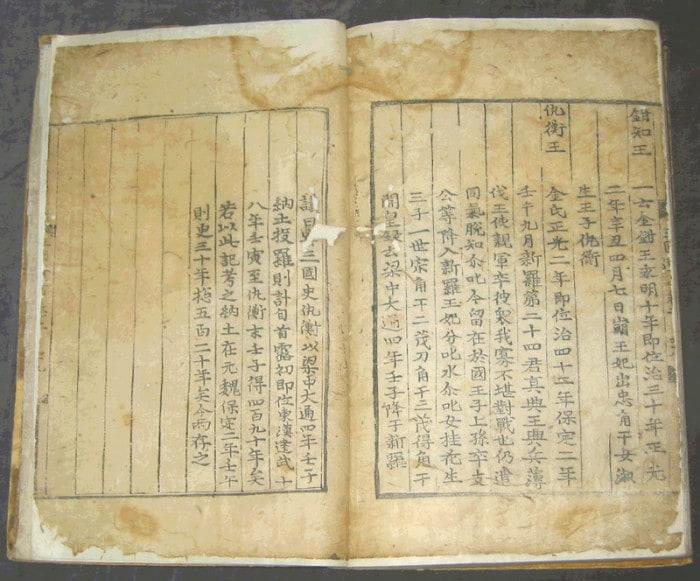

Nonetheless, we have a few pieces of literary evidence about early Silla maripgan chieftains like Nulji. There is mention of him in “Memorabilia of the [Korean] Three Kingdoms” (Samguk Yusa, 삼국 유사, 三國 遺事), compiled in the early 1200s. He’s also mentioned in “History of the [Korean] Three Kingdoms” (Samguk Sagi, 삼국 사기, 三國 史記), completed in 1145. From those texts, we have a few bullet-point raw facts — myths, actually — about his life and rule, but little context: both sources were written about 1,000 years after his reign.

The tales we have surrounding Nulji fall into two categories, and they’re enough to fill a TV soap opera. First, there are comparisons with his father, Naemul, and the ways in which monarchs would formally send their sons overseas as emissary-hostages, as tribute, or to build alliances. Second, and more importantly, there’s a glorious tale about Nulji’s attempts to bring his two brothers back from tribute-exile. It’s at the core of the stories about him in the “Memorabilia.”

The ‘Samguk Yusa,’ or ‘Memorabilia of the [Korean] Three Kingdoms,’ is one of our only sources of information on the lives and reigns of early Silla maripgan.

Nulji was the 19th Silla monarch and its third maripgan. In his third year on the throne (419), Jangsu of Goguryeo (장수, 長壽) (r. 413-491) (see box), head of the most powerful kingdom and strongest army in the region, asked that Nulji’s younger brother be sent to his court in Pyongyang for a “friendly visit.” Nulji wisely made peace with Goguryeo and sent off his brother Bohae (보해, 寶海), accompanied by an older man-servant named Kim Mu-al (김무알, 金武謁). His brother-tribute-prisoner stayed away for many decades, likely under coercion, until being rescued later in Nulji’s reign.

A similar story from the same source is told about Nulji’s father, Naemul. Naemul had to send Nulji’s brother, Mihae (미해, 美海), into exile to Kofun, probably to Tsushima Island, and Nulji himself had to send his own brother, Bohae, into exile to Goguryeo. Like father, like son.

It’s unknown whether these repeating stories, echoing from father Naemul to son Nulji, are just good story telling or if they’re actual historical events. Remember: the “Memorabilia” was compiled in Goryeo about 1,000 years after Naemul and Nulji ruled in Silla.

|

Elsewhere in Northeast Asia: During the mid-400s, Silla occupied only a small, dim corner of the Korean Peninsula. Goguryeo (37 B.C.-A.D. 668), however, was glorious, powerful and the ruling power in Northeast Asia. From its capital city in Pyongyang, by the 400s-600s Goguryeo ruled over much of today’s South Korea, all of North Korea, most of Manchuria, all of Liaoning Province, all of Jilin Province, most of Heilongjiang Province, many parts of eastern Inner Mongolia, and most of Primorsky Krai.

Jangsu of Goguryeo (장수, 長壽) (r. 413-491), the 20th Goguryeo monarch, enjoyed the fruits of all this glory. Coming to the throne at the age of 19, he reigned for 79 years over a glorious kingdom and died on the throne at the age of 98, leaving a much stronger state to his descendents. |

At this point, “Memorabilia” tells a touching, if quaint, tale of brotherly love, filial obligation, and honorable service to one’s monarch.

In the 10th year of Nulji’s reign (426), the maripgan was drinking with his courtiers and generals when he burst into tears.

“Oh! Woe is me! My father sent his beloved son, my brother, to Kofun as prisoner. Ever since I rose to the throne, my strong neighbor Goguryeo has warred against me and attacked our frontier time and time again. Believing that the king of Goguryeo wanted peace with Silla, I have now sent my own younger brother to his court. Now, he holds my brother hostage and will not let him return. Though I am rich and noble, tears flow from my eyes both day and night! If only I could see my two brothers again and we could apologize before the shrine of our father! I would be most happy!”

Conferring together, the other chieftains recommended that the “magistrate of Sapna County” rise to take on this delicate diplomatic task, a man named Bak Jae-sang (박제상, 朴提上) (363-419). Bak was dully brought before the maripgan and tasked with bringing home Nulji’s two brothers, one from Goguryeo, one from Kofun.

Bak said, “When the monarch is grieved, his subjects are disgraced. If the monarch is in disgrace, his subjects must die. If the subjects do only what is easy and do not undertake that which is most difficult, they are all disloyal. If they consider only their own lives, they are all cowards! Though I am an unworthy subject, I will faithfully execute this mission, given to me by Royal command.”

Nulji, of course, was appropriately moved and even deigned to drink from the same cup as Bak. So Bak left immediately for Goguryeo to save the first brother, Bohae. After sufficient twists and turns, as recounted with detail in “Memorabilia,” he returns home successfully with Bohae. Upon his brother’s return, Nulji said, “I have regained one arm of my body, one eye of my face, but I am still sad without the other!”

Bak said, “Your Majesty, just give the command and I will bring back Mihae, too!” He got on his hands and knees in front of the maripgan, struck his head twice on the floor as he made his kowtows, and departed on his quest, not even visiting his home. His wife pursued him on a white stallion, however, and when she arrived at the port, she found that he had just set sail. She wept and called out to him to return for a final farewell, but the loyal husband, a royal courtier, merely waved his hand and sailed on. With that, Bak sets out to save the second brother, Mihae, who had been sent to Kofun in 390 as a 10-year-old.

Just as before, like Odysseus sailing home, Bak faced trials and tribulations before sending Mihae home successfully. Upon returning to Silla, Nulji gave a great banquet at the palace in honor of his newly-returned brother, and proclaimed a general amnesty across the land. He conferred the title of Grand Duchess on Bak’s wife, and married Mihae to her daughter. As for Bak himself, he ended up facing quite a different fate. I highly recommend you get an English copy of “Memorabilia” and read the stories yourself. The tales are tall and wondrous.

Finally, today there stands a small stone monument to Bak on Tsushima Island, honoring him for his loyalty to his king.

That is a brief summary of the stories surrounding Maripgan Nulji. Read them yourself to get a sense of how modern people learn about the myths and deeds of their ancient monarchs. I’m sure that when his tomb is eventually discovered and excavated, we’ll learn more about his life and reign.

By Gregory C. Eaves

Korea.net Staff Writer

Photos: Cultural Heritage Administration

Sources: “A New History of Korea” by Ki-baik Lee and translated by Edward W. Wagner, “Samgukyusa” by Ilyeon and translated by Tae-Hung Ha, Doopedia, Naver, Wikipedia

gceaves@korea.kr

![[102nd March First Independence Movement Day] American journalist’s Seoul home to be opened to public](https://gangnam.com/file/2021/03/usr_1614255694426-218x150.jpg)