By Jeon Han

Photos = The Independence Hall of Korea

Illustration = Manus Eugune

A trading company in Andong (now Dandong), China, holds a distinctive place in the history of Korea’s independence movement.

Yilyungyanghaeng assisted the Korean Provisional Government in transporting weapons, delivering government funds and communicating with activists, playing a vital role in the campaign; the company was located in the same building as the provisional government’s Andong Transportation Branch Office. The British businessman who both owned the building and headed the company surprisingly worked behind the scenes to help Korea achieve independence. That man was George Lewis Shaw (1880-1943).

“It is human nature to sympathize with the countrymen of a fallen nation, and with the independence of minor nations being a world trend, it was natural for me to give advice to my Korean friends on their country’s independence movement,” Shaw said in an era when imperialism had reached its peak. Supporting Korean independence activists, he assisted them in any way he could.

Independence fighter Kim Gu mentioned in his autobiography Baekbeom Ilji, “Spending seven days in Andong, we headed to Shanghai on Yilyungyanghaeng’s corporate ship. When we passed by the Yellow Sea, Japanese guards followed us and blew their horns to warn our ship to stop. The British captain, however, kept sailing through the security zone at full speed in ignoring the guards. Four days later, we safely docked at the port of Hwangpo. We had 15 comrades on the ship.” The British captain who ignored the Japanese warning in the book is said to be Shaw.

Shaw’s company served as a connection point between the provisional government’s offices in China and Korea as well as a fortress to protect Korean activists and a military base to prepare for combat. The Briton’s involvement was critical for Korea, which means that he was a thorn in the side of Japanese colonial officials as recorded in Japanese documents. Japan could do nothing as Shaw and his company exercised extraterritorial rights. Finally, however, Japanese authorities jumped at the opportunity to arrest him when he visited the Korean city of Sinuiju, located between Andong and the Yalu River, to see his family.

Japan announced that Shaw was arrested for not possessing a passport but his support for Korean independence was the real reason. He was incarcerated at the notorious Seodaemun Prison in Seoul, which provoked strong condemnation from the British government. English-language newspapers in China and The London Times released articles that stirred anti-Japanese sentiment over this issue, and Shaw was eventually released on bail after four months.

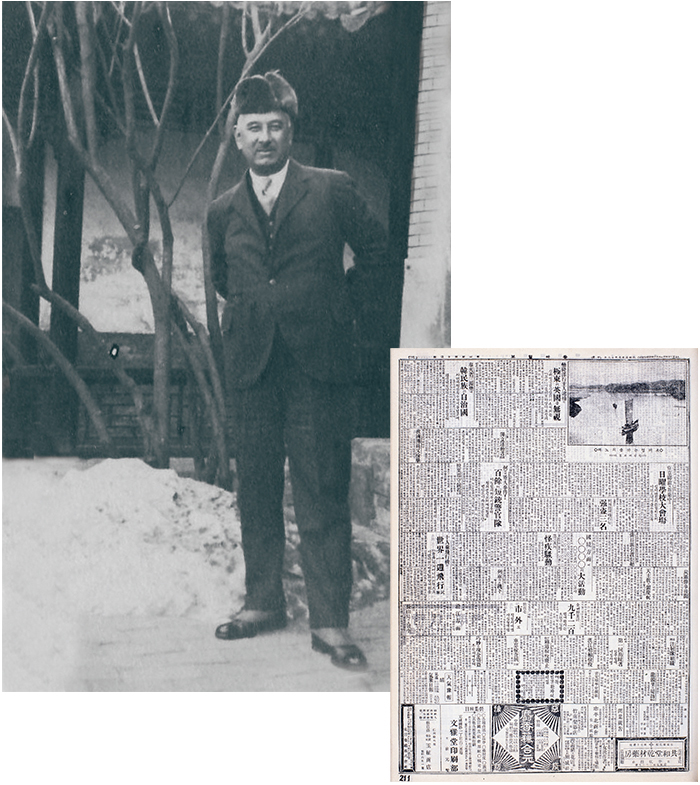

George Lewis Shaw (left) in Japan. The news article (right) that announced Yilyungyanghaeng’s owner was arrested

Active Role in Liberation Efforts

Despite Japanese intervention in his business and arrest and close surveillance, Shaw continued helping Korean independence fighters. His mother, wife and a daughter-in-law were all Japanese but this failed to deter him from supporting Korea. His zeal for Korean independence is said to have come from his Irish father, Samuel Lewis Shaw.

“Watch what’s happening in the world now. Ireland was liberated from Britain, and India’s independence is in sight. There’s no doubt that Korea will be the next independent country free from Japan’s colonialism. It won’t be long (before Korea’s movement) bears fruit,” Shaw said after his release from prison. Around this time, he pledged more actively involvement to help Korea gain independence, with his first move to that end being the relocation of his son from Tokyo and Yokohama to Fuzhou, China.

On Jan. 26, 1921, Ahn Chang-ho and Rhee Syngman, then president of Korean Provisional Government, held a welcoming party where they awarded Shaw the Golden Medal for Merit for his contributions. There, Shaw discussed plans for resuming operations at the Andong office and the independence movement in general, which had been discouraged after his arrest. The same year in May, he returned to Andong and pretended no longer having connections with Koreans while secretly resuming operations at the Andong office. His efforts enabled activists in the provisional government, the Korean Peninsula and activists based in Manchuria, China, to secretly send and collect information and deliver government brochures. In the meantime, Kim Mun-gyu, a staff member at Shaw’s company, attempted to sell “independence checks” to the wealthy in the Andong area to secure military funds.

Though Shaw’s generous support revitalized the Andong office, a heightened crackdown by Japanese colonial authorities led to the virtual collapse of the office and Kim’s arrest. Despite this, Shaw rehired Kim after the latter completed his prison sentence. The Briton also helped another employee of his, Kim Seung-bin, who was also an agent of the provisional government. Kim Seung-bin was sent to Seoul on a secret mission as part of the Korean independence movement.

Though Yilyungyanghaeng stayed afloat even at the height of Japanese imperialism, it eventually suffered massive financial difficulty. Thus Shaw was forced to close his company and leave Andong, concluding his 31 years of support for Korean independence and anti-Japanese activism. He died in Fuzhou, China, in 1943 at age 63.

The Independence Hall of Korea exhibits pictures of Shaw and his family to honor his contributions to Korea’s independence movement.

Commemorating Shaw’s Heroism

On March 1, 1963, the Korean government posthumously granted Shaw the Order of Merit for National Foundation. Unable to find his descendants at the time to accept the honor on his behalf, Seoul kept it for 49 years before finally giving it to his granddaughter, Marjorie Hutchings, on Aug. 16, 2012.

Upon receiving the medal, Hutchings told the government cable station KTV, “The legacy my grandfather has left behind is that no race, border or gender can restrain us from achieving good deeds. (To us,) this medal isn’t just a simple prize but an invaluable historic lesson.”

hanjeon@korea.kr

![[102nd March First Independence Movement Day] American journalist’s Seoul home to be opened to public](https://gangnam.com/file/2021/03/usr_1614255694426-218x150.jpg)